POSTS

How the Met Commercialized 'Camp'

Author: Lena Han

The 2019 Met spring exhibit, “Camp: Notes on Fashion,” is ambitious. Camp is an esoteric, abstract concept, unfamiliar to most Met visitors. As an aesthetic, Camp is less unified than Pop Art; as a movement, Camp is less historically-coherent than Impressionism; as an art form, Camp is less orthodox than Renaissance paintings. However, using framing from Susan Sontag’s seminal essay, “Notes on Camp,” the Met exhibit impressively communicates the meaning of Camp—an exaggerated, artificial, and anti-serious sensibility.

The exhibit opened three days after the 2019 Camp-themed Met Gala. It is organized in three stages: the first stage explores the historical development of Camp; the second stage uses excerpts of Sontag’s essay to characterize Camp; the third stage is a massive, sensational room filled with Camp fashion. The dozens of pieces exhibited in this final room are witty, extravagant, and self-aware.

Franco Moschino’s Ballerina Dress; Manish Arora’s Carousel Dress; Jeremy Scott’s Butterfly Ensemble

Franco Moschino’s Ballerina Dress; Manish Arora’s Carousel Dress; Jeremy Scott’s Butterfly Ensemble

Revisiting Sontag’s original essay, though, reveals how the Met adopted a sanitized, audience-pleasing version of Camp.

As Sontag explains, Camp is anti-high culture. Unlike the more message-driven works presented by many modern artists, Camp art is less “serious,” a rebellion against the etiquette of high culture. A dress with a carousel for a skirt, after all, does not strive to be nuanced; it is solely entertaining.

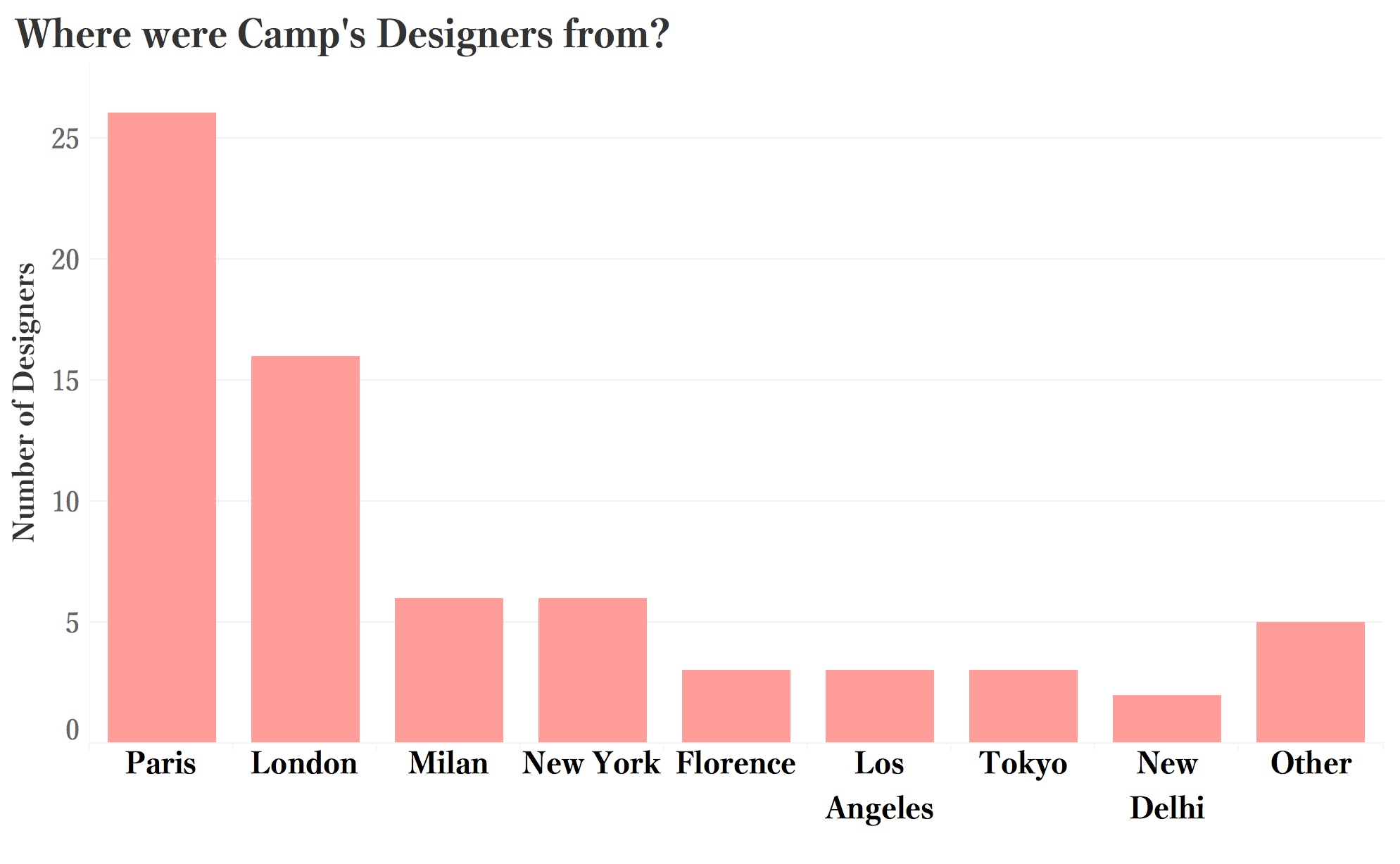

But the sentiment feels uncanny when those artists, supposedly defying the seriousness of high culture, are actually part of the elite. A glance at the featured designers reveals scores of luxury brands such as Balenciaga, Louis Vuitton, and Giorgio Armani. In fact, the below graph illustrates just how well the exhibit represented today’s fashion elite, hailing from the fashion capitals of the world. Over one-third of the designers hailed from Paris alone.

The Met website claims that “Camp has long been a space of diversity and inclusivity, as evidenced by the colorful and playful embroidery of Indian designers Manish Arora and Ashish, and the black camp of Patrick Kelly and Dapper Dan.” But on a map, the lack of diversity in the designers is even more striking. Out of the 75 designers featured, only 13 cities were represented. Not a single brand represented was based in Africa, South America, or Australia.

In this sense, the Met’s “Camp: Notes on Fashion” exhibit is a symptom of the broader inaccessibility of art museums. Even while many art museums are consciously trying to feature more diverse creators, they still pluck artists from the same elite fine arts institutions and cultural capitals. The Met exhibition faces the same problem; the exhibit outwardly supports inclusivity and the LGBT+ community but lacks a truly diverse cast of designers. When Sontag acknowledges that Camp taste is “by its nature possible only in affluent societies,” this is coded language that the fashion of racial minorities and the less-privileged is unwelcome in Camp.

In addition, Sontag writes that Camp is meant to be purely aesthetic, and as a result, “disengaged, depoliticized—or at least apolitical.” However, the Met politicized Camp in an easy, commercial manner. The exhibit was deeply conscious that it was displayed during pride month, during the year of the 50th anniversary of Stonewall; among the first works seen in the final exhibition room is a grandiose rainbow-colored cape. Furthermore, the exhibit feels inextricably tied to Hollywood, which has become a highly-political space.

Christopher Bailey for Burberry, Pride Cape

Christopher Bailey for Burberry, Pride Cape

Finally, Sontag reflects that “probably, intending to be campy is always harmful.” Yet the Met Gala asked celebrities to do exactly that: to dress with the theme of Camp. Their request diverged from the pure Camp sensibility and, frankly, just left many celebrities confused. Celebrities’ vastly different interpretations of Camp provided the impression that nearly everything could be considered Camp, cheapening Sontag’s thoughtful framework. The Gala failed to substantively interact with Camp fashion; instead, it only served to build hype for the Met exhibit.

Ultimately, the Met’s “Camp: Notes on Fashion” exhibit is entertaining and endlessly-flashy, but warps Camp into its most commercialized, institutional form.

Photos from the Met Website